Concord woman pleads with Legislature to protect victims of domestic and sexual violence

Nicole Kipphut speaks to New Hampshire state senators. Courtesy NHCADSV

|

Published: 10-30-2023 6:13 PM

Modified: 10-31-2023 2:24 PM |

Nicole Kipphut knows personally and professionally how intimidating it can be for victims to stand up for themselves at an abuser’s parole hearing.

Kipphut began her career as a victim advocate with the New Hampshire Department of Corrections when she was just 19, a calling that she followed after the sexual assault she endured as a child.

She went on to become the administrator of victim services where she advocated for survivors of sexual assault and domestic violence as offenders went through the parole and probation process.

As a skilled professional and a victim herself, she was called to a parole hearing that brought her feet away from the man who abused her – her father – for the first time since his incarceration.

“I was an experienced provider at that point for victim services but it was still shocking for me to get that notice in the mail and quite the process for me to engage as someone who has been before the parole board and knows the process well,” Kipphut said last week to a legislative committee studying the long-term impact of the New Hampshire adult parole system. “I can also say that it was empowering for me as a survivor but challenging and emotionally draining for me as well.”

At the first parole hearing in November 2020, her father had served 7 ½ years of his 10-year conviction. He denied accountability for his crimes, she said.

On Wednesday, Kipphut testified on behalf of the New Hampshire Coalition Against Domestic and Sexual Violence in front of a legislative committee led by State Sen. Rebecca Whitley, a Hopkinton Democrat.

Whitley sponsored the initial bill to create the committee to study the long-term impact of the New Hampshire adult parole system on offenders and victims. Since its creation in June, the committee has heard from the Department of Corrections, state and local agencies and advocates to develop recommendations to better the parole system.

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

Opinion: Public school standards overhaul will impact every facet of public education in NH

Opinion: Public school standards overhaul will impact every facet of public education in NH

With new plan for multi-language learners, Concord School District shifts support for New American students

With new plan for multi-language learners, Concord School District shifts support for New American students

With Concord down to one movie theater, is there a future to cinema-going?

With Concord down to one movie theater, is there a future to cinema-going?

Opinion: The Concord School Board can restore trust with residents

Opinion: The Concord School Board can restore trust with residents

Concord man charged felony criminal mischief following vandalism outside NH GOP event

Concord man charged felony criminal mischief following vandalism outside NH GOP event

Getaway driver in Winnipesaukee hit-and-run arrested

Getaway driver in Winnipesaukee hit-and-run arrested

The committee is expected to deliver a report on its recommendations by next month.

With a unique perspective both as a survivor and an advocate, Kipphut told Whitley that closure doesn’t come with sentencing or prison time. For some, it doesn’t come at all, but preparing for a parole hearing where most often offenders are granted early release is an extensive, draining process that can re-traumatize victims, she said.

“Victims do not necessarily feel closure at conviction, in fact, trauma is often ongoing and closure may occur at any point during the criminal justice process, from arrest to post-incarceration, and in some cases, closure may never happen,” Kipphut said. “There is no moment where victims automatically feel safe or healed.”

The parole board hears dozens of cases daily, most of which include victim impact statements that attempt to summarize the lifelong trauma, pain and stigmatization of being a survivor in three minutes while forcing the victim to sit less than 10-feet from their offenders, whom they likely haven’t seen since the criminal trial, Kipphut said. The hearings are quick and parole is granted more often than not.

In 2008, victims were allowed to provide impact statements privately and confidentially to the board without the presence of offenders, a tactic that provided space and safety.

In addition to allowing victim impact statements to be done privately, Kipphut recommended the committee also consider trauma-informed training for members of the parole board, more restorative practices, offender accountability, interagency collaboration and meaningful participation for victims in the post-conviction process.

“The crime is the first traumatic experience that victims face and how they heal is deeply impacted by the people and the systems they connect with after the crime,” said Lyn Schollett, executive director of the New Hampshire Coalition Against Domestic and Sexual Violence. “When they are re-traumatized, they are deprived of that opportunity for meaningful input in a case and the parole board isn’t getting all the info they need to make an informed decision.”

Scott Hampton, the director of Ending Violence and an educator for domestic and sexual abusers, advocated for better prison programs to mitigate and rehabilitate offenders once they leave prison.

“It appears that the highest risk time for re-offense is when they walk out of jail,” Hampton said. “It makes a lot of sense. Offenders have this sense of entitlement and privilege and will still believe that someone else got them arrested.”

To prevent offenders from being re-arrested, Hampton suggested structured programs with open communication about their behaviors and offenses that will help offenders take full accountability for their crimes, understand why they committed the offenses in the first place.

“If they get a taste of the program behind bars, when they get back into the community they’ll be more likely to continue the program and be more mindful of what those services are,” Hampton said. “Putting them behind bars doesn’t reduce their inclination to abuse, it reduces their opportunity to abuse.”

Though the Department of Corrections has programs in place for offenders, they’re more centered on anger management and substance abuse, not on the root causes of their behaviors. This allows them to be successful in improving their own lives but hasn’t done anything to reduce their risk of harming people once they’re released, Hampton continued.

The New Hampshire Adult Parole Board holds broad power to approve parole or revoke it. With that power comes direct financial implications for the state – it costs more than $50,000 a year to house a prisoner at the Department of Corrections and just a few hundred dollars to supervise someone out on release.

Kipphut was there to remind the committee of the emotional costs.

“I have been to and sat through hundreds of parole hearings and supported hundreds of victims,” Kipphut said. “As much as I would love to believe there is a lot of closure when it comes to sentencing offenders and sending them to prison, it doesn’t end there.”

Voice of the Pride: Merrimack Valley sophomore Nick Gelinas never misses a game

Voice of the Pride: Merrimack Valley sophomore Nick Gelinas never misses a game With less than three months left, Concord Casino hasn’t found a buyer

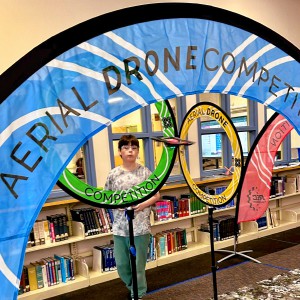

With less than three months left, Concord Casino hasn’t found a buyer Kearsarge Middle School drone team headed to West Virginia competition

Kearsarge Middle School drone team headed to West Virginia competition Phenix Hall, Christ the King food pantry, rail trail on Concord planning board’s agenda

Phenix Hall, Christ the King food pantry, rail trail on Concord planning board’s agenda